Participants

Stavros Lazaris (CNRS, Paris)

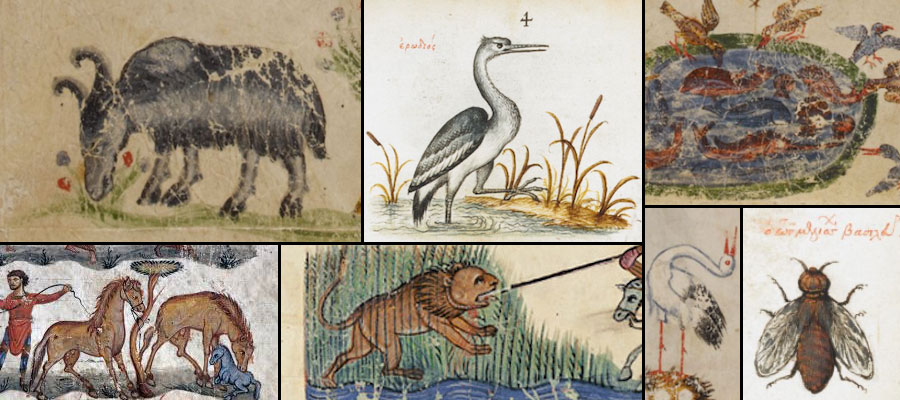

Animals in Byzantium, To Comfort Humans and Their Souls

Animals have recently become important as subjects of history as part of the overall “animal turn” which has developed within several academic disciplines. Much of this interest stems from two works (Singer 1975; Derrida, 2006). While these were works of philosophy – the first ethics, the second epistemology –, the increased attention they have brought to animals has encouraged several academics within the humanities and social sciences (psychology, sociology, law, literary studies...) to re-evaluate the place of non-human animals within their research, studying them both in their interactions with humans and as worthy objects of enquiry in themselves. This trend has not left history untouched; while some significant work was done by Keith Thomas (Thomas 1983) and Robert Delort (Delort 1984) in the early 1980s, the last ten years have been particularly fruitful (Kalof 2007; Roche 2008; Baratay 2012; Moriceau 2012; Campbell 2014). In addition to these publications, 2013 saw the journal of the philosophy of history, History and Theory, devotes an entire issue to animals in history, while the 2000s have already seen several conferences devoted to the theme of animals in medieval and ancient history (Rome 2002; Lyon, 2005; Strasbourg, 2009), and 2016 saw at least a further four (Rouen 2016; Lyon 2016; Leeds 2016; Munich 2016).

In several of these studies, it was clearly established that the animal has its own story that deserves further attention. Through four components (exploited animals; animals for leisure; animals as symbols; animals as objects to be studied), I propose to present a synthesis dedicated to the Byzantine man and his relationship with animals, or rather to the relationship between animals and men in Byzantium, because it’s the animal’s point of view that can tell us about men and their perception through space and time.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baratay 2012

É. Baratay, Le point de vue animal. Une autre version de l’histoire, Paris, 2012.

Campbell 2014

G.L. Campbell, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life, Oxford, 2014.

Delort 1984

R. Delort, Les animaux ont une histoire, Paris, 1984.

Derrida, 2006

J. Derrida, L’Animal que donc je suis, Paris, 2006.

Kalof 2007

L. Kalof, ed., A Cultural History of Animals, Oxford, 2007.

Leeds 2016

The Animal Turn in Medieval Health Studies, International Medieval Congress (Leeds 2016).

Lyon, 2005

Le médecin initié par l’animal (Lyon, 2005).

Lyon 2016

1st International Symposium on Animals in Ancient Egypt (Lyon, 2016).

Moriceau 2012

J.-M. Moriceau, L’homme contre le loup: une guerre de deux mille ans, Paris, 2013.

Munich 2016

Animals at Court (Munich, 2016).

Roche 2008

D. Roche, La culture équestre de l’Occident, Paris, 2008.

Rome 2002

Man and Animal in Antiquity (Rome, 2002).

Rouen 2016

L’animal et l’homme (Rouen, 2016).

Singer 1975

P. Singer, Animal Liberation, New York, 1975.

Strasbourg, 2009

Le cheval dans les sociétés antiques et médiévales (Strasbourg, 2009).

Thomas 1983

K. Thomas, Man and the natural world: changing attitudes in England, 1500-1800, London, 1983.

Florin Leonte (Palacký University Olomouc)

Communication and Public Justice: How Animals Talk in Late Byzantium

This paper explores how animals were constructed as agents of political negotiation as well as individual subjects in the literature of late Byzantium. During this period several texts that featured dialogues and debates between animals circulated widely at the Byzantine court. Among them, anonymous compositions like the Book of Birds and the Entertaining Tale of Quadrupeds echoed the conflicts between various political factions vying for authority in Constantinople. However, these literary encounters between animals not only revealed historical information hidden under intricate references but they also held an underlying symbolic effect that pointed to the Byzantines’ views about the animal world. In discussing such issues, I will bring a literary approach to the late Byzantine writings of animal debates together with perspectives from ethology. This paper will thus contribute to the study of the Byzantine attitudes towards animals and to the conceptualization of animals as parts of a view of court society that prized competition and ambition (φιλοτιμία).

My investigation will proceed from the assumption that in Byzantium the animal world was regarded as a large depository of signs that could yield an understanding of the divine order. As a result, representations of animals in a polemical environment often suggested their ethical engagement underlined by a didactic approach. This idea can be reinforced by the overview of the differences between the literary animal dialogues, on the one hand, and the late Byzantine polemical and satirical dialogues, on the other hand. Such a comparison, which will consider the circulation of the ancient Platonic and Lucianic dialogic models, also allows us to better understand the specificity of the animal debates.

Another observation underlying the present analysis is that these texts had a strong taxonomic focus. The texts reflected the court τάξις in Byzantine Constantinople with its intricate structures and shifting allegiances. Animals were usually grouped into opposing factions characterized by their natural habits (e.g. herbivores vs carnivores). Doubtless, this systematization of types of animals reflected an aristocratic view of the court. There were animals that received more praise and were considered to be more prestigious than others. This situation clearly echoed the court hierarchy informed by kinship relations and ideas of responsibility.

Taking these observations into account, this paper will further argue that the type of communication present in the dialogic texts of late Byzantium involving animals are different from those in other regular dialogues, a highly popular genre in late Byzantium. In addition, this paper will demonstrate the late Byzantine dialogues like the Poulologos or the Entertaining Tale of Quadrupeds also mark a shift from the representation of animals as objects to that of beings capable of subjective experience and of engagement in moral actions.

Przemysław Marciniak (University of Silesia in Katowice)

(Micro)History of Byzantine Insects

The gnat, they say, is like the elephant, so I will argue that the flea is like the panther, states Michael Psellos (Or.min.). His three pseudoscientific treatises on fleas, bedbugs, and lice are a curious testimony to Byzantine experiments with zoological and literary traditions. They combine Aristotelian knowledge with the Lucianic tradition of writing paradoxical enkomia. Yet, they have not attracted much interest from students of Byzantine culture, most likely because they do not contribute to our understanding of Byzantine zoological knowledge.

The thirteenth book of the 10th century compilation Geoponika includes information about various insects (such as locusts, ants, and fleas) and advises how to exterminate them. Unfortunately, none of the almost fifty manuscripts of this text are illustrated, so there is no visual evidence (there are illustrations of insects in the much earlier Vind. Med. gr. I). Yet, Byzantine literature offers a surprising selection of texts on insects – the three above- mentioned, unstudied, pseudoscientific treatises penned by Michael Psellos on fleas, bedbugs, and lice, poems on the spider and the ant by Christopher of Mytilene, and a psogos of a fly by Eugenios of Palermo. Human interaction with insects concerns two intertwined areas of interest: biophysical reality and “the abstract world of aesthetics, fantasy, and metaphysical speculation." Byzantine writers often merged these two spheres to produce new meaning - a detailed description of an animal is used to convey a more symbolical meaning. This twofold yet complementary, approach to animals is especially visible in texts, which are located between the real and the imaginary as they include a detailed description of an animal, which, in turn is used to express a symbolic meaning.

Christopher of Mytilene describes a spider in a very detailed way to ponder God’s might, while Eugenios’ description of a fly, a subversive take on Lucian’s paradoxical enkomion, is conducted to prove his participation in Greek paideia. Therefore, my presentation will study the role, which the insect imagery played in the literary and cultural imagination of the Byzantines in the 11th and 12th centuries.

Tristan Schmidt (Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz)

The 'Leo-Pardos' and the Enemy of Double-descent: Manuel I's Hunts as Political Metaphors

One of the prominent features of Komnenian imperial representation is the praise of the emperor as a successful hunter. Following traditions that can be traced back to ancient concepts of ideal rulership, the image of the emperor defeating dangerous animals related particularly well to the general appreciation of martial virtues within the military élite of the time. In the imperial context, hunting descriptions had the intention to portray the emperors as the most virtuous and able of warriors, alluding to aristocratic role models, like the popular narrative of the hero Digenis Akrites. Beyond these unambiguous references, however, they often provided further subtexts, turning episodes about imperial hunts into similes for current political and social conflicts.

Particularly interesting cases are two descriptions of emperor Manuel I hunting lions and pardaleis. One of them appears in the history of Ioannes Kinnamos, the other one in the inaugural speech as Hypatos tōn Philosophōn by Michael Anchialu, later Patriarch of Constantinople. Although not explicitly related to each other, both descriptions show striking similarities. A thorough analysis of the violent encounters between the emperor and the predatory beasts, as well as a precise examination of the animal species involved, reveal more layers of meaning, beyond the classical description of the successful hunter. Both authors place their episodes in the context of concrete political and military conflicts – in one case the alleged rebellion of the Prōtostrator Alexios Axuch, in the other a war against Serbians and Hungarians – using the stories of the encounter between man and animal as foreshadowing similes.

Uncovering the concepts related to the animals involved, as they appear in ancient and medieval zoological as well as Christian interpretations, explains their specific literary functions. Kinnamos purposely introduces the Medieval concept of the Leo-Pardos, a hybrid between lion and the ominous Pardalis, with regard to the ethno-religious background of the “rebel” Axuch. The two types of Pardaleis in Michael’s speech, attested already in Ancient zoological literature, were meant to characterize the two upcoming military adversaries. Furthermore, despite the strong literary character of the episodes, it has to be asked to what extent these episodes could still be perceived as reality by the contemporaries.

The examples show how authors and orators, familiar with both the day-to-day politics and the traditional learning of their time, transferred and transformed knowledge on animals in a political context, providing evidence for a lively, interdiscursive exchange in public discourse at the Komnenian court.

Katarzyna Warcaba (University of Silesia in Katowice)

Session chair