Participants

Session 1

Saskia Dirkse (Harvard University/University of Basel)

The Death of the Monastic Everyman in Seventh-Century Homily & Tale

This paper considers two early seventh-century literary treatments of a topos popular in monastic literature of the time: the deathbed interrogation of a swooning monk. In such scenes, a monk in the throes of death is called to give account for his actions in life before an unseen demonic host. The dramatic spectacle unfolds before a stricken and fearful audience of fellow monks, who are able to catch only half of the exchange (the answers but not the questions) and at the moment of death are left painfully uncertain about the outcome of the moribund’s ordeal.

The motif likely originated in the late antique tradition of edifying tales, where in the early seventh century it is used to great dramatic effect in Klimakos’s Ladder of Divine Ascent and Anastasios’s Tales of the Sinai Fathers, which urge their listeners to contemplate their own mortality and to consider how they might best prepare for the relentless interrogation that they too will face at that dreadful, inevitable moment.

Around the same time that accounts of this “final conversation” are gaining currency in the tales tradition, we find a number of homilies – the most important among these being the Sermo in Defunctos, traditionally though not conclusively also attributed to Anastasios of Sinai – that also use the motif as a narrative platform from which to deliver an urgent memento mori about the importance of repentance and the daily remembrance of death.

The fact that we have these parallel treatments of the same subject, in a language and culture that routinely borrowed literary tropes and “metaphrased” their stylistic register both up and down, makes this a good case study and one that allows for a more quantifiable than impressionistic comparison. And, while the main comparison will be between this sermon and these tales, the motif is also expressed (often with identical or very similar wording) in a number of other contemporary and near-contemporary sources which offer additional illumination of the subject.

We will first consider broader questions of genre and audience: how is the motif transformed when it passes from the simple and concise language of the tales into the explicit, yet carefully oratorical, expression of the homily? Which parts of the topos are accentuated, expanded or omitted as they appear in each treatment and to what effect? How does the sermons’ liturgical context affect both their form and content?

Then we will proceed to a more concrete comparison of the two styles – examining not only the choice of genres but the use of nouns vs. verbs, the abstract vs. the tangible, hypotactic vs. paratactic syntax, choices and uses of vocabulary, morphological difference and more – as neatly and clearly against each other as the material allows.

Both treatments of the motif are meant for oral performance and tend to the same lesson, but by different routes – the low road and the high. And, however we today may judge the quality of their results, both attempts were justified by scriptural precedent, the one author following the example of the Evangelists, who present their doctrines through a narrative almost approaching drama, the other working in a more expository and self-consciously rhetorical, Pauline vein.

Scott Johnson (University of Oklahoma)

Chair

Grigory Kessel (Marburg University)

A Syriac Monk’s Reading: A Perspective on the Monastic Miscellanies

As in other Christian traditions, reading played an important role in Syriac Christianity. However, in contrast to these other traditions – particularly the Greek- speaking one – the development of reading practices and book culture within the Syriac Christian tradition has not yet received the attention it deserves. As heirs of the ancient Mesopotamian scribes, Syriac Christians placed great value on books and on reading. And, as with many other aspects of their Christianity, the Syriac attitude towards reading and learning had certain traits unique to its tradition.

In the field of Byzantine Studies it is hagiographic works that provide the most interesting material for the study of book culture in a monastic milieu. And the lives of the Syriac monks provide intriguing evidence about monks’ reading practices. Thus, for example, we read in the life of Rabban Bar ‘Edta (d. 611) that he memorized the magnum opus of Nestorius, The Book of Heraclides (521 pages in the modern edition!), as well as learning the entire Bible by heart and the works of Abba Isaiah, Mark the Monk, and Evagrius of Pontus.

A scholar of Syriac Christianity is therefore in a very fortunate position, as we have in our possession the actual products that reflect the changes and developments that took place within the Syriac monastic tradition from the sixth century onwards. A large number of Syriac manuscripts have been preserved, drawn from collections of texts that were selected and copied by the scribes for their brethren.

Miscellanies were the main vehicle for the transmission of monastic literature and were deemed essential for a monk’s spiritual formation. Already in the earliest extant examples (dating to the sixth century) we can detect unique content, which characterizes this type of literature during its entire history and which sets it apart from the non-Syriac traditions. Such collections of texts thus offer us a unique glimpse into the Syriac monastic milieu of their day. They show us, for example, which texts were given preference for copying and which texts fell out of usage after a period of circulation. Through miscellanies we can observe clearly how Syriac monasticism was making a shift from admiration of the Byzantine monastic tradition to the establishment of its own extensive corpus.

The paper will therefore consider Syriac miscellanies containing ascetic texts as a possible source for the study of intellectual activity in Syriac monasteries of the seventh century. We will attempt as well to reveal the particular character and defining features of the miscellanies of that period, in contrast to those of other times and places.

Nicholas Marinides (University of Basel)

Organizer and presenter

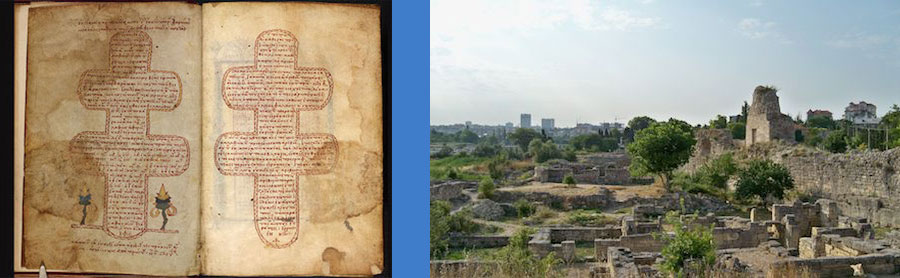

The Pandektes of Antiochos: A Neglected Witness to Learned Culture at the Lavra of Mar Saba in the Early Seventh Century

The Pandektes of Antiochos of Mar Saba is one of a large dossier of writings that were provoked by the Persian conquest of Jerusalem and surrounding events in the first third of the seventh century. It is often cited by historians for its few but valuable details about contemporary historical events, and occasionally used by patrologists to unearth new patristic citations. But the work’s purpose and its Sitz-im-Leben in a monastic culture of intensive reading and conversation has been largely neglected.

The work consists of a series of ethical discourses, prefaced by a letter to an abbot Eustathios and concluded by a lengthy penitential prayer. Eustathios directed a monastery named Attalinê, in Ankyra of Galatia, where Antiochos had begun his monastic life before moving to Mar Saba. Due to the Persian invasion, the monks of Attalinê had been forced to leave behind their monastery, library included. Eustathios requested of Antiochos a digest of the Scriptures, as an edifying vade mecum for the homeless monks.

Each of the 130 chapters deals with a particular virtue or vice, addressing it primarily through patristic quotations, followed by a collection of supporting scriptural texts. It is not exactly a florilegium, given Antiochos’ active role in paraphrasing and adapting his texts. The patristic sources include both pre-Nicene Fathers—Ignatios of Antioch, Polycarp of Smyrna, Hermas of Rome, Irenaios of Lyons, the pseudo- Clementine Epistles to Virgins—and post-Nicene ascetical authors, including Evagrios of Pontos, Diadochos of Photikê and John of Karpathos. The selection must reflect to some degree the availability of books in the monasteries in the environs of Jerusalem. It thus provides us with evidence for how authors at the end of late antiquity drew on the developing patristic canon and interpreted it for their own didactic purposes.

Antiochos primarily speaks to the monastic readership for which the work was requested, but he also sought to make it useful to a wider audience. At certain points he hints at oral delivery; perhaps Antiochos tried the discourses out on locals before sending off the polished form to the distant Galatians. Furthermore, in the course of the work, Antiochos provides evidence for the ubiquity of interactions between monks and laypeople, including frequent conversations on spiritual topics, and seeks to advise monks on how such visits should be conducted in order to edify laypeople while preserving monastic detachment.

With its traces of both written citations and spoken teachings, the Pandektes offers an important window into both the literate and oral culture of Palestinian monasticism in the early seventh century. It also shows how the two were organically interwoven and mutually influential, and how the fruits of such interaction might be collected in a book that was sent far away, in a monastic and literary network extending to Galatia. As such, it is an important test case for reading circles and cultures in the early Byzantine period.

Alexis Torrance (University of Notre Dame)

The Ambiguity of the Book in the Work of John Climacus

The complex and multilayered literary sophistication of John of Sinai’s Ladder of Divine Ascent has been the subject of a recent fruitful study by Henrik Rydell Johnsén. He demonstrates the depth and breadth of John’s rhetorical and literary skill in which ancient forms of discourse (like the moral treatise) are adapted and put to highly effective use for a Christian ascetic audience. This paper will begin by summarizing Johnsén’s significant contribution to our understanding of reading culture in Byzantine monasticism at “the close” of late antiquity. Building on this, the paper will turn to some of John of Sinai’s own intimations regarding one of the key issues at stake: the nature and role of books.

Concentrating on relevant passages in both the Ladder of Divine Ascent and To the Shepherd, the ambiguous role of the book will be highlighted. As a tool and weapon in the ascetic arsenal, the book is in one sense indispensable. Aside from the more obvious benefit of the book as conveyor of Scripture and the writings of the fathers, we also learn in Step 4 of the key role notebooks could have: attached to the belt, they were repositories for the monk’s daily thoughts which could then be read or shown to one’s spiritual guide. In the brief vita of John by Daniel of Raithou, the activity of writing books was likewise viewed as beneficial in the combat with acedia. However, there is a noticeable strand in John’s work that questions the ultimate need for the book, going so far as to posit an ascetic ideal that dispenses with all books. Three contexts in which such a view is deployed will be examined. The first, in Step 5, juxtaposes having a “living image” for repentant ascetic life with the need for books. The second, in Step 25, shifts the ideal mode of ascetic learning away from books to a kind of immediate apprenticeship to Jesus Christ, more particularly to the humility of Christ. While the book is negated here, the locus of such apprenticeship, interestingly, is nonetheless conceived as an inscription inscribed directly within the body of the believer. Finally, in To the Shepherd, a similar motif emerges at the outset, according to which the true spiritual guide should have no need of books, just as teachers, John claims, are clearly defective if they give instruction using others’ writings. Having analyzed these instances, the presence of an overall ambiguity with regard to the book will be emphasized. It will be argued, moreover, that the more negative understanding of the book is in fact dependent upon its continuing presence at some level (if only as “the tablet of the heart”). In particular, the positive assessments surrounding books in John of Sinai paradoxically serve to give the book an integral, even definitive, role in the bringing about of an idealized mode of ascetic learning and knowledge divested of books, a role exemplified by John’s own literary masterwork, the Ladder.

Session 2

Benjamin Anderson (Cornell University)

Co-organizer and presenter

The Oxeia Without Emperors

The Oxeia (“the sharp”) was a medieval name for the hill in Constantinople on which Süleymaniye Camii now stands. According to the fifth-century Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, the surrounding area was distinguished by the highest density of domestic building within the city. Of the various written sources that mention the Oxeia, the earliest and by far the most informative is the seventh-century collection of miracles worked by Saint Artemios from his crypt within the church of Saint John the Forerunner, which was located on or near the hill. To follow a distinction drawn by Albrecht Berger, “the Oxeia” names a “topos,” not a “quarter.” However, the miracles of Artemios present an image of a distinct local culture rooted in this place.

The miracles provide an unusually wide range of data regarding the neighboring landmarks (porticos, shops, and baths), and the identities both of the visitors to the Church of Saint John and the locals whom they encountered when they arrived. The miracles’ dramatis personae exhibits a robust diversity of professions (deacons, physicians, actors, sailors and tanners, to name a few) and origins (from Alexandria and Rhodes, for example, and various other places in Constantinople, such as Kaisarios and “ta Kyrou”). At the same time, it is distinguished by the absence of emperors (the reigns of Maurice, Heraclius, and Constans II are invoked only as chronological markers) and the scarcity of imperial officials. Furthermore, although the tenth-century patriographers ascribe the construction of the church of the Forerunner to the Emperor Anastasios, this attribution results from a confusion with the eighth-century patriarch of the same name who owned a house by the Oxeia. The seventh-century miracles are silent on the matter of the church’s patronage.

The miracles of Artemios provide a rare (perhaps unique) contemporary witness to the emergence of one of the nuclei about which urban culture began to crystallize in the sixth century. As Paul Magdalino has argued, those same nuclei sustained the life of the capital throughout the eighth and ninth centuries, a phenomenon also attested in the case of the Oxeia by the toponym’s prominence in further early medieval sources. The absence of imperial initiative from the miracles’ representation of local culture might reasonably prompt a re-evaluation of the forces that drove the creation of these nuclei. Do we need an emperor’s intervention to explain the emergence of the Oxeia as a distinct locality?

Eric Ivison (College of Staten Island CUNY & CUNY Graduate Center)

The Lower City Church at Amorium as a Byzantine Neighborhood (6th–9th Centuries)

The ecclesiastical complex designated the Lower City Church (or Basilica A) is located near the center of the site of Byzantine Amorium, a city of the late Roman province of Galatia II Salutaris, which in the 7th century became headquarters of the military and civil administration of the new command of Anatolikon. The excavated parts of the church complex extend to approximately 2,250 square meters, with survey indicating that additional, unexcavated structures extend beyond the excavation areas on all sides. Given the known extent of the complex, it seems likely that it was a significant landmark in the city plan.

The Lower City Church complex was first constructed in a number of building campaigns during the late 5th and 6th centuries, at a time when Amorium was undergoing significant urban reconstruction and expansion. The early Byzantine complex comprised of a basilica church, with attached atrium, baptistery, and other buildings linked by corridors and courtyards. Between the 6th to 9th centuries the church complex underwent significant addition and modification, a period that ended with the destruction of the complex and the city in the Arab attack of 838. Repairs and additions were made to the basilica during these centuries, but just as significant was construction in the surrounding complex, where open spaces were filled in with new buildings of mud-brick and cobblestone, including a winery and a wine press vat.

By exploring the development of the Lower City Church complex from its foundation through the early 9th century, this paper explores the religious, social and even commercial use of space, and also seeks to reconstruct the social profile of its users and occupants. By doing so, this paper seeks to interpret the Lower City Church complex not only as an ecclesiastical monument, but also as a multifunctional and evolving “neighborhood” in its own right, that was used and adapted to meet the needs of successive generations. This paper explores questions of the church’s religious status and function, and thus seeks to understand what communities or social groupings used the complex. This paper argues that on a civic level, the church complex served as a communal focus of civic religious ritual and cult veneration. However, on a local level, the church complex also served its resident ecclesiastical community and the surrounding urban quarter. The evolution of the Church complex from the 6th to 9th centuries therefore offers insights on how this “neighborhood” and its inhabitants responded to urban, social and economic change during this period.

Fotini Kondyli (University of Virginia)

Co-organizer and presenter

Shared spaces-shared lives: community building in the neighborhoods of Middle Byzantine Athens

The beginning of the Athenian Agora excavations in the 1930s by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens marked the discovery of the Byzantine settlement overlying the ancient Greek Agora. During that first decade of excavations alone, hundreds of Byzantine houses were brought to light together with public spaces, churches, burials, streets and industrial spaces. The excavations in the Athenian Agora continue to this day, revealing more about Athens’ Byzantine past with each field season. Despite the volume of the excavated material and its significance, only a couple of Byzantine houses have been published and a synthesis of the discoveries in the Athenian Agora pertaining to Middle and Late Byzantine urban living has yet to be attempted. Thus, the idea of Byzantine Athens as a small and rather insignificant town continues to prevail in scholarship and the extraordinary body of evidence form the Agora excavations remains unexploited.

This paper seeks to rectify this situation and contribute to a better understanding of Middle Byzantine Athens based on unpublished material from the Athenian Agora excavations. It argues for a bottom –up approach to the study of the city and points to the importance of micro scale spatial and social relationships in reconstructing urban environments and accounting for the participation of all social actors in the making of cities. Hence this paper presents preliminary results from the study and reconstruction of Middle Byzantine neighborhoods located to the north and northwest side of the Athenian Agora and discusses their spatial and temporal qualities. Moving beyond house typologies, it follows the biography of houses and their surrounding spaces from the 10th to the 13th c. It specifically explores the coexistence of residential areas with burial sites, public spaces and industrial features that speak to the diverse role of neighborhoods as spaces of economic, social and political interaction. Particular attention is paid to architectural changes, repurposing of spaces, and placemaking activities at the level of the neighborhood that reconfigure the function and meaning of spaces and ultimately condition urban living. This paper argues that the shared rights, responsibilities and experiences involved in the building and maintenance of the city’s neighborhoods enhanced collectiveness and allowed Athenians to self-identify through membership in their local communities. It furthermore suggests that the variable and irregular Imperial control of the Byzantine periphery created a power vacuum that ultimately gave local communities at Athens the autonomy to become the architects, administrators and protectors of their own cities.

Kostis Kourelis (Franklin and Marshall College)

Chair

Jordan Pickett (University of Pennsylvania)

Structuring Neighborhoods with Water in Late Antiquity

This paper examines how water infrastructure and management contributed to neighborhood formation in Late Antiquity, with particular attention to the variable behaviors of churches as regards water planning at the service of city-dwellers. A three-dimensional, bipolar model is offered as an heuristic to help categorize a wide spectrum of historical behaviors that played out in cities across the Later Roman Empire, with regard to water. If imagined as a Cartesian plot, its x axis might be defined as the measure of state control over water resources, as indicated especially by the relationship of water networks to fortifications and other strategic locations within cities. Its y axis might be defined as the degree to which churches were integrated into municipal water networks (whether as suppliers or merely down- line consumers); its z axis as a measure of the variety of hydraulic installations around churches (for liturgy, water-storage, industry, bathing, etc.).

Case-studies from Apamea and Jarash are offered by which this model is explained, and its broader applicability is demonstrated. At Apamea, state control over water intra muros was maintained by placing distribution equipment for an inner aqueduct (6th century) within the line of fortifications; churches at Apamea offered little in the way of storage, and were integrated into water networks only as consumers with fountains, akin to elite residences. At Jarash, state control over water is less visible, and church-planners worked with a freer hand: the Cathedral-St Theodore complex adopted an aqueduct water supply from the obsolescent Temple of Artemis, and also converted Roman rainwater drains descending from the temple platform into supplies for newly built cisterns, around which sprang up a neighborhood of middling residences, food preparation areas, and industrial installations.

From these introductory examples, we underline the variability of water management practices by which the church did or did not contribute to neighborhood formation: where the church acted only as a consumer, akin to a large residence, the church played little role in restructuring Late Antique neighborhoods away from Roman precedents. However, where the church more actively engaged in water planning, we might see how the church could both encourage a break away from Roman drainage- and display-oriented water management models, towards storage and utility, and also stimulate the development of new, middling, production- oriented neighborhoods within cities.

Adam Rabinowitz, Larissa Sedikova (The University of Texas at Austin, National Preserve of Tauric Chersonesos)

Life and Death on the Block: Neighborhood, Space, and Social Practice in 12th/13th-century Cherson (Crimea)

Traditional evidence for Byzantine urban life is rich, but heavily biased toward text and unevenly distributed in space and time. Documentary papyri elucidate neighborhood life in Early Byzantine Egypt; regulatory texts like the Book of the Eparch reveal the ideals of urban administrators in Middle Byzantine Constantinople; works of literature like the Prodromic poems add additional color to our picture of daily life in the City in the 12th and 13th centuries. None of these sources, however, offer a holistic account of how life was lived by a group of people in a particular neighborhood at a particular time. Archaeological research has been better able to address this question, but it has largely been limited to the excavation of single neighborhoods at sites like Athens or Corinth, or to the exploration of ecclesiastical and aristocratic topography in continuously-occupied centers like Thessaloniki or Constantinople itself. These limitations make it difficult to identify the boundaries between central planning, neighborhood norms, and individual initiative in commerce, housing, and religious practice. Furthermore, the archaeological record rarely allows us to reconstruct the human population of a neighborhood, instead forcing us to use buildings and objects as proxies for status and identity.

The site of Cherson (ancient Chersonesos, at the southwest tip of Crimea) is an exception. Most of the city’s 40-hectare urban core was extensively rebuilt in the 11th and 12th centuries, and then much of it was violently destroyed in the 13th century and never reoccupied. About a third of that area has been excavated over the last hundred and fifty years, and as a result the site provides an unparalleled opportunity to explore the workings of a number of different neighborhoods across a century or two of continuous use. The joint excavations of the Institute of Classical Archaeology and the National Preserve of Tauric Chersonesos in a block in the city’s South Region between 2001 and 2006 offer an especially exhaustive case-study of the intersection between private life, economic activity, and religious space in a well-defined neighborhood of the 12th and 13th centuries. The construction and modification history of the buildings in the block affords us a chance to explore both public control of development and private choices about the use and division of residential and commercial space. The presence of a chapel within the block itself and the use of this chapel for the burial of the block’s residents informs us about both religious practice – especially in the context of the broader religious topography of the city – and the people in the neighborhood, from whose remains we have reconstructed demographic, pathological, and dietary information. Finally, the fiery destruction of the block around the middle of the 13th century has preserved extensive evidence for the patterning of social practice in this neighborhood at a particular moment, which can in turn be compared to evidence from other neighborhoods destroyed at the same time across the city.