Past Recipients

2022–2023

Georgios Deligiannakis, Open University of Cyprus

Project: The Open University of Cyprus Church Excavation Project in Ancient Messene

The city of Messene was a major urban settlement of the Hellenistic and Roman Peloponnese, and a regional economic and cultural hub for the Messenia region. Messene adapted quickly to the Roman realities and became a close ally of the Romans, governed by wealthy local elites with strong ties to Italy. The city shows signs of resilience during the 3rd and early 4th century, when a good number of public buildings and wealthy urban mansions remained in use. Messene was struck hard by the famous 365 CE earthquake. The seismic destruction and wider later 4th and early 5th century crisis in the region caused significant change in the city and the region. We need to reach the late fifth and sixth century to have a clearer picture of the Early Byzantine, by then Christian, city of Messene, its history and its monuments, even though a small Christian community lived here already by the mid-3rd century.

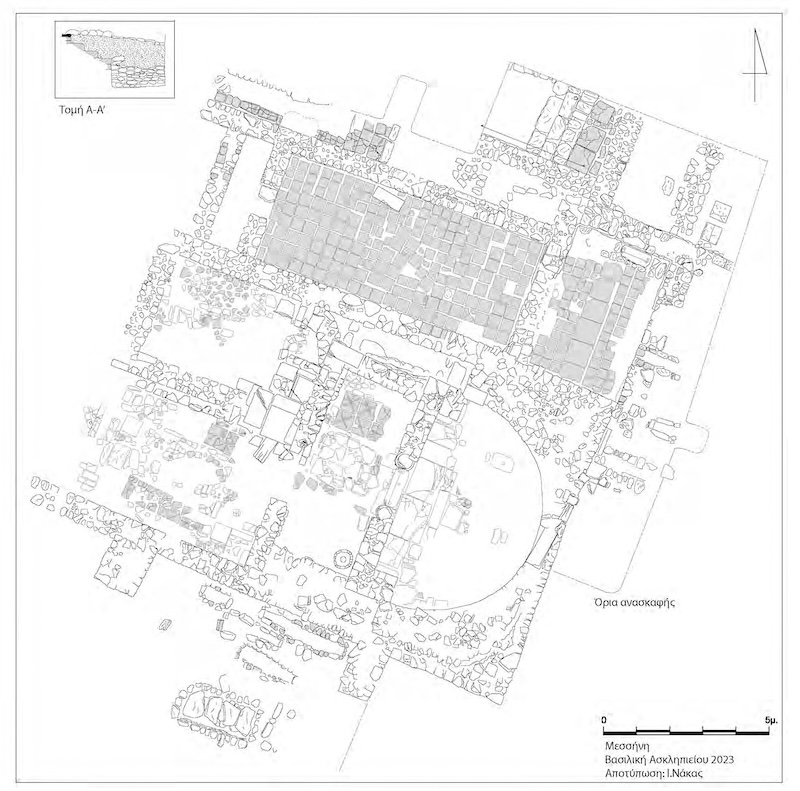

The only Early Christian basilica that has been fully excavated is located near the theater and was built in the mid-6th century. Setting out to complete the picture of the early Byzantine built landscape of the city and connect the dots of city’s Christianization, we decided to excavate a large building, lying east of the Asklepieion complex that also appeared to be an apsidal building and which had never been excavated. In four excavation seasons (2020-23) the Open University of Cyprus (OUC) team under the aegis of the Society of the Messenian Archaeological Studies have carried out systematic excavation on the site. By subsidizing travel and maintenance costs, our project offered the opportunity to recent graduates of OUC and other universities to obtain hands-on experience in excavation and to carry out small-scale research on specific categories of the material.

The first results of our research lead to the conclusion that the building originally belonged to a spacious ecclesiastical complex of the Early Byzantine period with a large semi-circular apse (6.35 m. chord) and side annexes that incorporated earlier Roman/Late Roman structures. The church was part of the early Byzantine settlement, named as the Asklepieion neighbourhood. The site remained in use for about half a millennium. The early church appears to have been destroyed before the 10th/11th century CE, when it was repaired and rebuilt as a small chapel occupying the exedra of the apse. Progressively a medieval cemetery evolved around the chapel and over the ruins of the Early Byzantine ecclesiastical complex. Pottery and metal finds suggest that the last phase of use of the chapel when also most of the burials were opened should be dated to the 12th-14th century. A characteristic late Middle Byzantine bronze ring depicting a military saint was among the grave finds. Amidst the numerous cist tombs, the remains of agricultural and other activities (e.g. a grape treading floor) can also be identified in the area. Skeletal remains are carefully stored for future study, while regarding particular types of finds we are in contact with experts, whom we regularly invite to inspect the material. In 2023 geophysical prospection was carried out on the site to be used as a guide for future trenches.

Figure 1: Aerial photo; excavation site looking NW (front); part of the Asklepieion complex (back)

Figure 2: Plan of the excavation site (2023)

Figure 3: View of the ecclesiastical complex from the west

Figure 4: View of the floor of the ecclesiastical complex made of reused flooring pieces

Figure 5: Grave 29, cist grave encased under a monumental floor construction; it contained one inhumation

Figure 6: Bronze ring depicting military saint found in medieval grave

Figure 7: Dr. M. Arvanitis during geophysical scanning

Asil Yaman, University of Pennsylvania Museum

Project: PhoenixByz: Contextualizing the Serçe Limanı within a Rural Byzantine Landscape. Project co-director: Anna Sitz, Universität Heidelberg

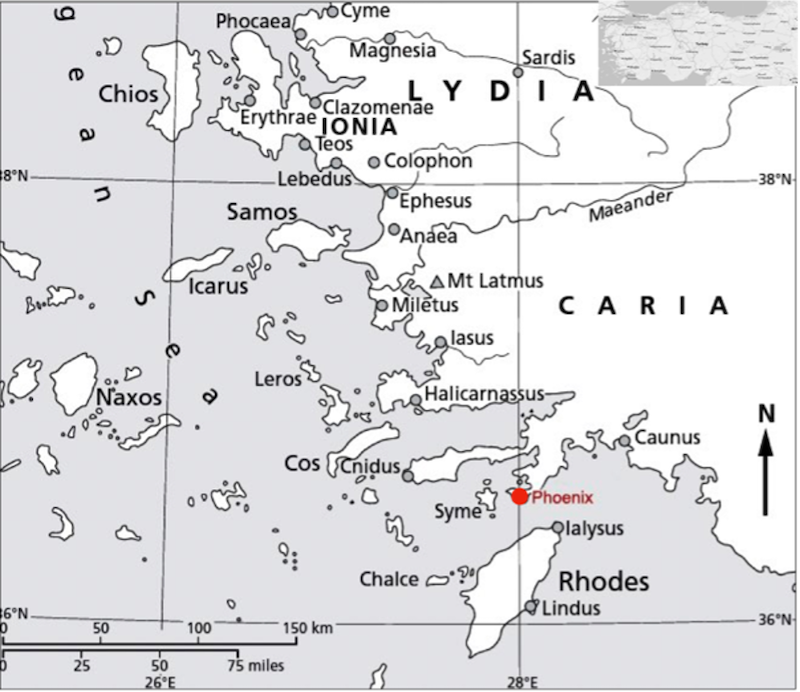

A Byzantine merchant ship carrying spectacular glass cargo sank off the coast of southwestern Turkey in the 11th century, close to the Serçe Limanı. The glass was likely intended to be sold in a city, but if any of the ship’s crew managed to swim to shore, they would have found themselves in a very different environment: the rural and rugged mountainous area now known as the Bozburun peninsula, with the ancient site of Phoenix (Φοῖνιξ) at its center. The region today is likewise agricultural. But change is rapidly coming, with touristic infrastructure springing up along the coast. This rural Byzantine landscape, largely undocumented, is under threat of being lost forever (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Serçe Limanı from the north. Photo: Asil Yaman

Figure 2: Website of the Phoenix Archaeological Project: www.phoenixprojesi.com

In order to understand this landscape before it’s too late, the Phoenix Archaeological Project (PAP), directed by Dr. Asil Yaman (UPenn Museum) continued its survey work in 2022 with the support of a Mary Jaharis Project Grant. PAP is a “new gen” project, meaning that we not only draw on the latest technology (including laser scanning and 3D landscape modeling), but also that we treat the landscape holistically, documenting every period of human occupation (Figures 2, 3). This diachronic perspective offers greater insight on individual periods.

Figure 3: Map of the southwestern coast of Asia Minor. Photo: Asil Yaman

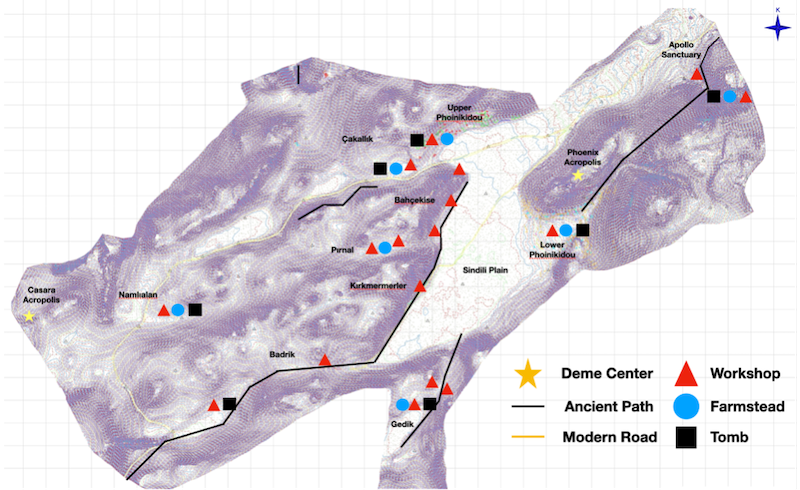

In 2022, a subproject of PAP, PhoenixByz (co-directed by Dr. Anna M. Sitz, Universität Tübingen) surveyed 450 hectares of rural land, documenting the relationship between people and landscape (Figure 4). We found 17 agricultural installations (farmsteads, presses, cisterns), with ceramic sherds suggesting use of some in the Hellenistic period and others in the Byzantine period. The distribution of these agricultural facilities near paths leading to the Serçe Limanı and other harbors suggests a de-centralized model of production and transportation: these were small-scale farmers producing for themselves and perhaps bringing their own goods to port, rather than organized estates with centralized collection of goods. The landscape was not only exploited for production: we also discovered a Byzantine chapel on a mountainside not far from a press site (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Topographical model with agricultural production units and related spaces discovered in 2022. Source: PAP Archive

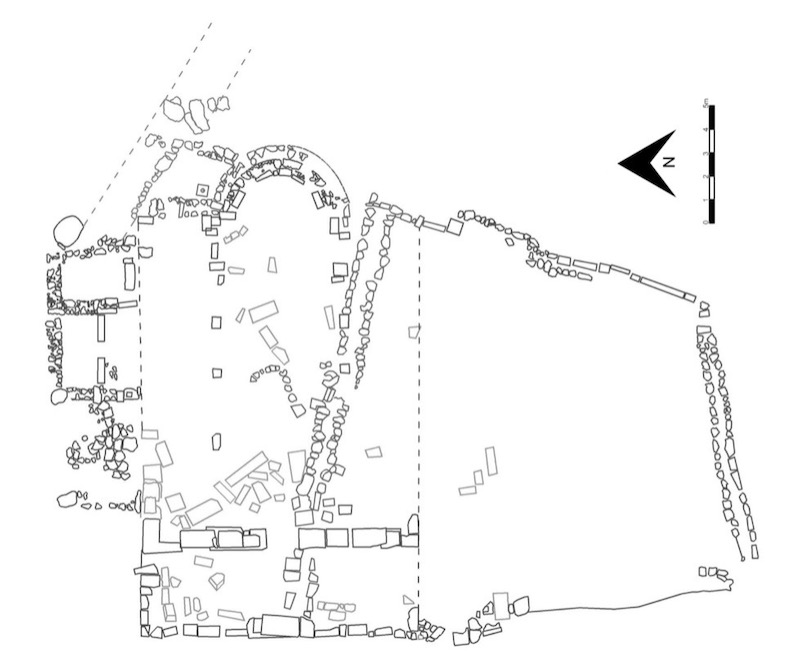

Figure 5: Apse of a rural Byzantine chapel discovered in 2022

Closer to the site of Phoenix itself, we initiated the excavation of a church, the Kızlan Church (Figures 6, 7). It has long been known that this church was built of spolia (reused building material), but our excavations revealed a particular construction approach. The church was built in the 5th century CE, based on ceramic finds, from blocks of an ancient sanctuary of Apollo, but it also incorporated other blocks, including grave stones from a nearby necropolis. It became clear that the use of spolia was a planned feature of the construction: the gravestones are integrated throughout, indicating these were not used only when the blocks of the ancient temple had been exhausted (Figure 8). Moreover, the incorporation of inscribed blocks at visible spots (doors, windows, narthex) suggests that the ancient Greek texts were desirable decorative elements. Exceptionally, even an inscription to Apollo, preserved in crystal-clear lettering, was incorporated in a doorway (Figure 9).

Figure 6: Aerial photo of the excavation loci of the Kızlan Church. Source: PAP Archive

Figure 7: Plan of the Temple-Church with later walls. Source: PAP Archive

Figure 8: The excavation team at work at the Kızlan Church (Photo looking east). Photo: Anna Sitz

Figure 9: The inscription of Apollo at the north entrance into the Kızlan Church

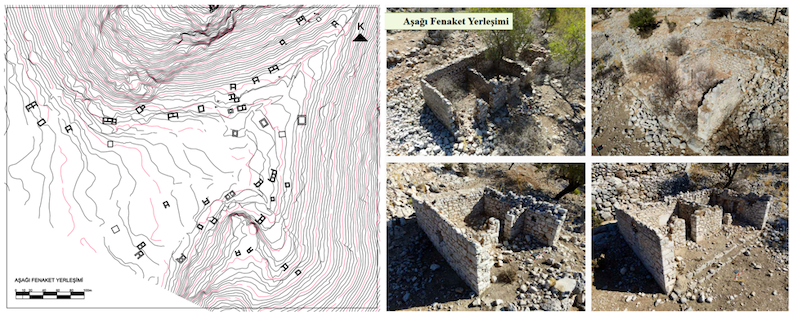

Our project also surveyed an abandoned early modern Greek village, Fenaket (Figure 10). A PhD student is writing her dissertation on the vernacular architecture of this village. The village revealed more ancient spolia. One house is known as the Yazıtlı Evi (the Inscribed House) because of the ancient Greek inscriptions built into its walls. Our survey made a surprise discovery that revealed why: the house was built on top of an earlier chapel, itself built of ancient inscribed spolia.

Figure 10: Lower Phoinikoudi (Fenkaet). Plan and representative houses. Source: PAP Archive

Finally, as a “new gen” archaeological project, PAP is committed to incorporating locals into our academic research. This includes knowledge dissemination and training in the importance of ancient monuments, as well as exchanges of more ephemeral cultural heritage, for example, at a traditional gastronomy event we hosted this year (Figure 11). Afiyet olsun (enjoy)!

Figure 11: Traditional local food at the PAP gastronomy event. Photo: Anna Sitz

2021–2022

Bilge Ar, Istanbul Technical University

Project: Documentation of the Northern Church and Contextualizing the Relations Between Religious Structures in St. Thecla (Meryemlik) Archaeological Site

A pilgrimage site dedicated to St. Thecla of Iconium is situated 2 km south of Silifke (Seleucia ad Calycadnum) in Mersin, Turkey. The site is locally referred as Meryemlik and is well known for its three large scale churches and numerous cisterns, most of which are products of imperial donation. The site seems to have had its active years limited to the Late Antiquity. Studies so far conducted on religious structures of Meryemlik have focused on two of the three monumental scale churches. In terms of its possible domed architecture, the “Cupola” Church is being considered as a predecessor of the domed basilical plan, and had been subject to several discussions in terms of its connections with Constantinopolitan styles. The Basilica of St. Thecla, causing awe with its size, is also mentioned in sources, both in terms of its architectural features and in its relation with the saint, especially with the rock-cut church underneath it, housing the cave that Thecla lived and later disappeared in.

On the northernmost and highest location of the site lies the remains of another equally monumental religious structure “the Northern Church”. The building, situated in this prominent location, is identifiable as a three nave basilica, with dimensions roughly 60 m x 30 m, with its apse oriented towards east-southeast. A schematic plan of the building has been documented by Herzfeld in 1907. The plan and the capitals and ambo platform visible on site were included in his 1930-publication with S. Guyer. Following this date, no other study has been conducted on the Northern Church, and later publications included only similar notes, and images taken from this early publication.

The Northern Church was included in the St. Thecla (Meryemlik) archaeological site survey program for the first time in 2021 in accordance with this project funded by the Mary Jaharis Center for Byzantine Art & Culture. In order to evaluate the building together with its surroundings and discover its topographical relations, detailed documentation work was conducted on the church and its surrounding remains, its relationship with the ancient road in the west, structures between this road and the church, the terrace walls on its northern slopes, the numerous rock-cut cisterns and chamasorium type tombs in the east and the west, and the architectural ornaments on the surface.

After the completion of the documentation process, the project aims to evaluate the processional routes connecting the religious structures and the relationship of the religious monuments with topography and with their surrounding structures, in an attempt to reconstruct the religious usage of the site.

Aerial photo of the Northern church

Architectural plastic elements in the Northern Church: Columns of the atrium, ambo, a column capital

2020–2021

Günder Varinlioğlu, Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University

Project: Wealth through Limestone: An Island Quarry Landscape in Late Antique Isauria

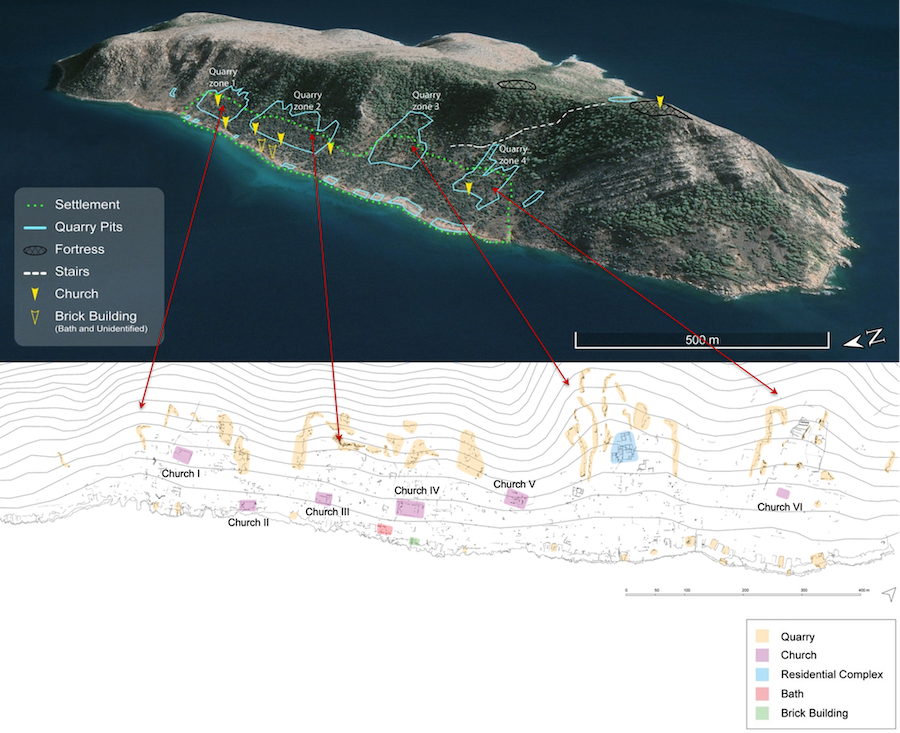

As the largest known source of building material in southern Türkiye, the limestone quarries of Dana Island (ancient Pityoussa) were the focus of the final campaign of the Boğsak Archaeological Survey-BOGA (Figure 1). Unusually for a quarry, the island preserves remains of the settlement known as Pityoussa, which developed during the fourth-eighth centuries CE, when seven churches were built, six being on the coast and one on the summit (Figure 2). This industrial settlement must have benefited from the intensification of the Eastern Mediterranean maritime networks after the foundation of the new imperial capital in Constantinople. The ambitious building activity across the province required large amounts of ordinary building material, such as the low-quality clastic limestone of Dana Island. Furthermore, the province of Isauria was known for its itinerant building crews who worked on several construction projects in the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as in Italy. The quarrying industry and trade on Dana Island were a product of this burgeoning demand.

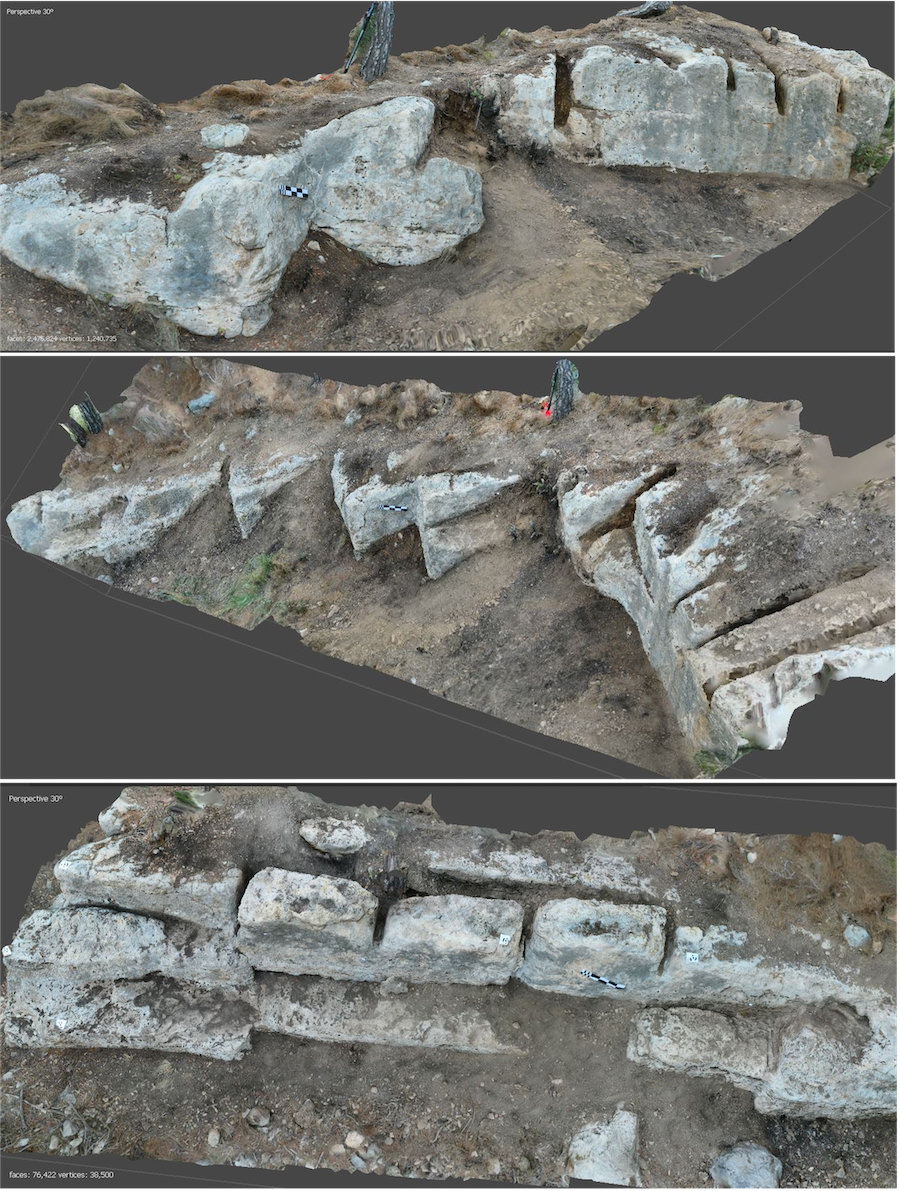

Field investigations in 2021 prioritized the study of a particular industrial area (see figure 2, quarry zone 3) that stands out by a residential complex partially carved out of bedrock and occupying the lower corner of the largest quarry zone of the island (Figure 3). For the documentation of the quarries, the BOGA team used terrestrial photogrammetry, or Structure-from-Motion, in conjunction with field sketches and measurements. The fieldwork focused on four large quarries, which have relatively high vertical faces and well-preserved quarrying features, such as different types of stone extraction channels, tool marks, and partially cut stone blocks. Through this method, the team created accurate 3D models (Figure 4) that help us understand the techniques and tools of stone cutting and transport, the types of stone blocks produced in the quarries, and the volume of stone extraction. The extensive survey in the periphery of this industrial zone and across the coastal settlement resulted in the discovery of new quarries located further up the slope, beyond the elevation of 80 m asl documented previously. The team also located another church at the southeastern end of the coastal settlement and terrace houses with well-preserved rock-cut niches.

This project continues to investigate the social, economic, and technological aspects of the procurement of ordinary building materials, a topic that has received little attention so far in Byzantine Studies. It sheds new light on questions ranging from labor cost and organization to spatial relationships between habitation, religious practices, and industrial activity. It attempts to interpret the processes by which Dana Island quarries became integrated into wider Mediterranean maritime networks and the likely role of the island’s resources in the formation of the Isaurian building industry.

Figure 1: Dana Island and its environs (map by Kıvanç Başak)

Figure 2: Quarries of Dana Island. Google Earth image (top, by Hilal Küntüz); settlement and quarry map (bottom, by Nihan Arslan and Hilal Küntüz)

Figure 3: The residential complex (DI.ST001-002) and quarries (orthophoto by Kıvanç Başak)

Figure 4: Quarry Q003. Images produced from the 3D models created using photogrammetry (field documentation by Ruveyda Ceylan and Doğukan Karaman; data processing by Hilal Kesikci)